The Resilient Farm and Homestead:

An Innovative Permaculture and Whole Systems Design Approach by Ben Falk

An Innovative Permaculture and Whole Systems Design Approach by Ben Falk

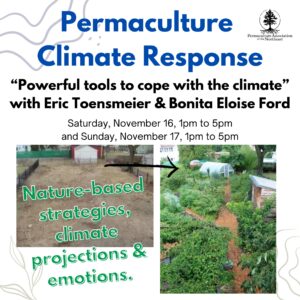

There’s still time to register for our Permaculture Climate Response online workshop!

Read the full PDF article below (works best on a computer) or click on the “download” button to save the file (best for cell phones). PAN recently shared three new

New article featuring information from the Apios wiki–written by Eric Toensmeier, edited by Bonita Eloise Ford.

Pawpaw: A Favorite Native Edible Plant Read the full PDF article below (works best on a computer) or click on the “download” button to save the file (best for cell

by Shira Lynn You know those high maintenance yards where plants don’t touch — where each specimen is surrounded by a mulch moat living the American dream of ruling one’s

Be part of our board! We want to grow our board. We are seeking people who: Are interested in permaculture (professional and beginner permies are welcome). Value equity, diversity, and

PAN is excited to co-host this event with Permaculture Institute of North America. More info.

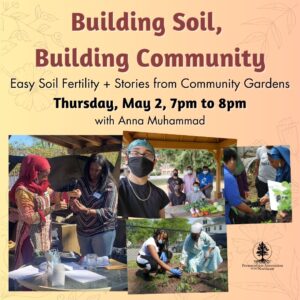

We are so looking forward to this webinar with Sister Anna on May 2. Read more and join us!

By Shira Lynn Taking care of plants and soil is an act of love—an expression of our commitment to growing a healthy and resilient community. At the heart of ecological

We are delighted to host our first Queer Permie Social on January 19. Check it out…

We are so excited to host this online event with Monica Ibacache on November 21! Learn more and join us!